From October, 1781, to October, 1782.

After the death of my father, we of course changed houses, and I remained with my mother till the spring of 1782, and was a day-scholar to Parson Warren, my father’s successor. He was not very deep, I believe; and I used to delight my mother by relating little instances of his deficiency in grammar knowledge,-every detraction from his merits seemed an oblation to the memory of my father, especially as Parson Warren did certainly pulpitize much better.

Somewhere I think about April, 1782, Judge Buller, who had been educated by my father, sent for me, having procured a Christ’s Hospital Presentation.

I accordingly went to London, and was received by my mother’s brother, Mr. Bowdon, a tobacconist and (at the same time) clerk to an underwriter.

My uncle was very proud of me, and used to carry me from coffee-house to coffee-house and tavern to tavern, where I drank and talked and disputed, as if I had been a man.

My uncle lived at the corner of the Stock Exchange and carried on his shop by means of a confidential servant, who, I suppose, fleeced him most unmercifully.

He was a widower and had one daughter who lived with a Miss Cabriere, an old maid of great sensibilities and a taste for literature. Betsy Bowdon had obtained an unlimited influence over her mind, which she still retains. Mrs. Holt (for this is her name now) was not the kindest of daughters but, indeed, my poor uncle would have wearied the patience and affection of an Euphrasia.

He received me with great affection, and I stayed ten weeks at his house, during which time I went occasionally to Judge Buller’s. My uncle was very proud of me, and used to carry me from coffee-house to coffee-house and tavern to tavern, where I drank and talked and disputed, as if I had been a man. Nothing was more common than for a large party to exclaim in my hearing that I was a prodigy, etc., etc., etc., so that while I remained at my uncle’s I was most completely spoiled and pampered, both mind and body.

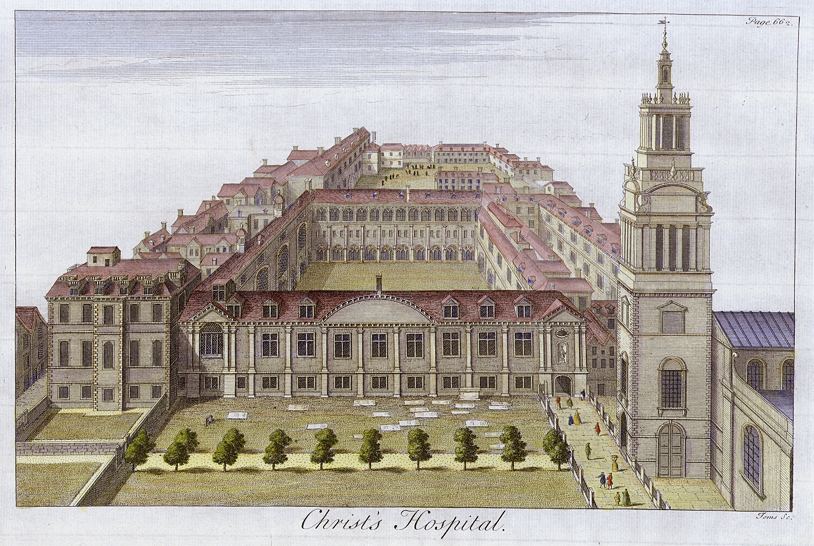

At length the time came, and I donned the blue coat and yellow stockings and was sent down into Hertford, a town twenty miles from London, where there are about three hundred of the younger Blue-Coat boys. At Hertford I was very happy, on the whole, for I had plenty to eat and drink, and pudding and vegetables almost every day. I stayed there six weeks, and then was drafted up to the great school at London, where I arrived in September, 1782, and was placed in the second ward, then called Jefferies’ Ward, and in the under Grammar School.

There are twelve wards or dormitories of unequal sizes, beside the sick ward, in the great school, and they contained all together seven hundred boys, of whom I think nearly one third were the sons of clergymen. There are five schools,—a mathematical, a grammar, a drawing, a reading and a writing school,—all very large buildings.

When a boy is admitted, if he reads very badly, he is either sent to Hertford or the reading school. (N. B. Boys are admissible from seven to twelve years old.) If he learns to read tolerably well before nine, he is drafted into the Lower Grammar School; if not, into the Writing School, as having given proof of unfitness for classical attainments. If before he is eleven he climbs up to the first form of the Lower Grammar School, he is drafted into the head Grammar School; if not, at eleven years old, he is sent into the Writing School, where he continues till fourteen or fifteen, and is then either apprenticed and articled as clerk, or whatever else his turn of mind or of fortune shall have provided for him.

Two or three times a year the Mathematical Master beats up for recruits for the King’s boys, as they are called; and all who like the Navy are drafted into the Mathematical and Drawing Schools, where they continue till sixteen or seventeen, and go out as midshipmen and schoolmasters in the Navy. The boys, who are drafted into the Head Grammar School remain there till thirteen, and then, if not chosen for the University, go into the Writing School.

Two or three times a year the Mathematical Master beats up for recruits for the King’s boys, as they are called; and all who like the Navy are drafted into the Mathematical and Drawing Schools, where they continue till sixteen or seventeen, and go out as midshipmen and schoolmasters in the Navy. The boys, who are drafted into the Head Grammar School remain there till thirteen, and then, if not chosen for the University, go into the Writing School.

Our diet was very scanty. Every morning, a bit of dry bread and some bad small beer.

Each dormitory has a nurse, or matron, and there is a head matron to superintend all these nurses. The boys were, when I was admitted, under excessive subordination to each other, according to rank in school; and every ward was governed by four Monitors (appointed by the Steward, who was the supreme Governor out of school,—our temporal lord), and by four Markers, who wore silver medals and were appointed by the Head Grammar Master, who was our supreme spiritual lord. The same boys were commonly both monitors and markers. We read in classes on Sundays to our Markers, and were catechized by them, and under their sole authority during prayers, etc. All other authority was in the monitors; but, as I said, the same boys were ordinarily both the one and the other.

Our diet was very scanty. Every morning, a bit of dry bread and some bad small beer. Every evening, a larger piece of bread and cheese or butter, whichever we liked. For dinner,—on Sunday, boiled beef and broth; Monday, bread and butter, and milk and water; on Tuesday, roast mutton; Wednesday, bread and butter, and rice milk; Thursday, boiled beef and broth; Saturday, bread and butter, and pease-porritch. Our food was portioned; and, excepting on Wednesdays, I never had a belly full. Our appetites were damped, never satisfied; and we had no vegetables.